SESAH Annual Conference 2023

Administrative Reverie: Master Plans as Institutional Dreamwork

Conference Presentation, September 2023

This paper theorized master planning as an administrative act distinct from architecture and urban design,

one that mobilizes design expertise in support of the anticipative, projective, and imaginative faculties of

bureaucratic institutions. Once adopted, master plans channel institutional growth and change but also, to

varying degrees, manage and control architecture itself. Unlike most urban design proposals, master

plans tend to establish stylistic standards to enforce aesthetic cohesion in excess of spatial arrangement.

Producing a master plan requires a blend of omniscience and naivete, a stance that often causes

designers to suspend disbelief in order to offer grand, abstract visions. Drawing from research in the

collection of institutional planning consultant, author, and educator Richard P. Dober—particularly his

work on the initial master planning phase of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Center in Atlanta—this paper

argues that as architects took on master planning projects in the post-WWII years, a phase shift took

place that was as much methodological as it was professional. On the one hand, designing master plans

allowed architects to champion abstract composition using closed spaces and volumes, an approach that

was otherwise forbidden by functionalist dogma during the mid-twentieth century. Indeed, unlike other

scales of modernist design, these projects’ success is often judged purely by the persuasiveness of their

visual communication. On the other hand, master plans are often accompanied by hundreds of pages of

bureaucratic paperwork documenting existing conditions, itemizing needs, and justifying projections—

work that only specialists like Dober could effectively complete. As opposed to the infrastructural

approach taken by engineers or the technocratic approach of administrators, what is it that designers

bring to the practice of master planning? Why do these administrative reveries remain compelling despite

their frequent failure to be realized in recognizable form?

Contact sheet showing master planning consultant Richard P. Dober meeting with Coretta Scott King and members of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Center board, early 1970s (Dober Collection, Frances Loeb Library, Harvard Graduate School of Design) .

Contact sheet showing master planning consultant Richard P. Dober meeting with Coretta Scott King and members of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Center board, early 1970s (Dober Collection, Frances Loeb Library, Harvard Graduate School of Design) .

SAHANZ/UHPH Joint Conference 2022

A Moderate’s Megastructure: Edward Larrabee Barnes and the Planning of

SUNY Purchase, New York, 1967-71

Virtual Conference Presentation, November 2022

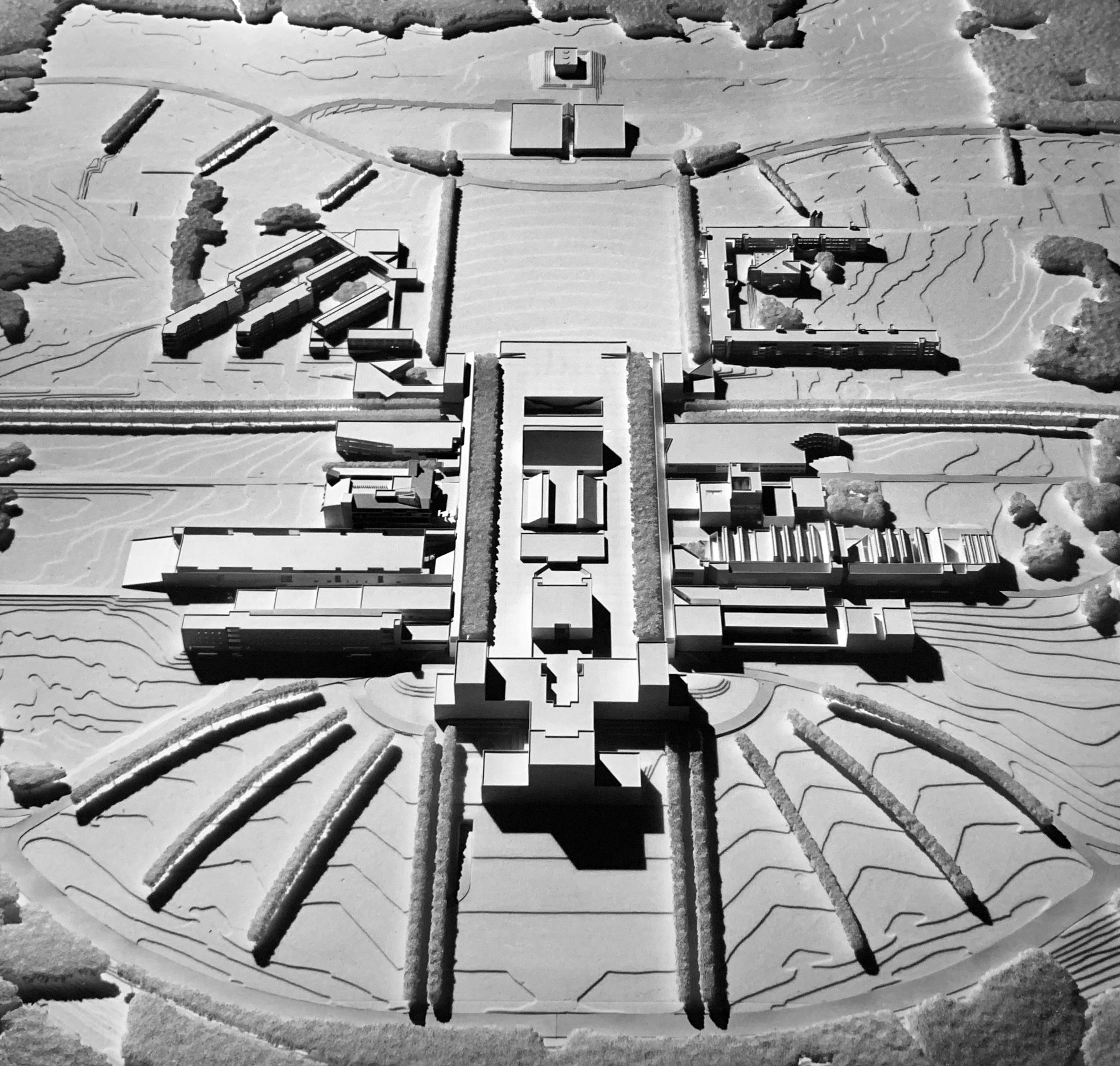

In

the 1960s United States, university campuses were seen as testbeds for urban

spatial and social relations, and their master plans were therefore a prime opportunity

for their designers, usually architects, to realize urbanist visions. Initiatives

from this period remain staggering in their scale and architectural ambition. The

State University of New York system a massive expansion on more than 50 campuses

across the state during the tenure of Governor Nelson Rockefeller. The most

ambitious of its new campuses was its flagship arts college at Purchase, about

25 miles north of Manhattan, master planned by architect Edward Larrabee Barnes.

Mimicking Thomas Jefferson’s famous design for the University of Virginia, the

master plan symmetrically arrayed buildings for different disciplines around a

massive paved plaza. Along the plaza’s centerline, Barnes himself designed an

interconnected complex for students’ everyday needs. Flanking this was a

concrete-framed arcade onto which buildings by other leading architects abutted.

Barnes’ plan challenged these architects with prescriptive requirements

intended to engender a cohesive and consistent atmosphere, including the

dictate that all buildings be clad in the same gray-brown brick, and that all

openings be framed in dark gray glass and metal trim. These prescriptions were

a negative image of “architecture” as understood in this particular place and

time: a stable regulatory regime within which architects could be liberated,

within reason. Barnes’ design was a moderate’s version of a megastructure, intended

to manage creative impulses—both those of other architects and of art students—rather

than set them free. If the eternal problem of planning is to offer a vision for

the future loose enough to adjust to the unexpected, then the vision offered

here was the controlling gaze of a paranoiac. Is the master plan inevitably a

tool of management, or can it be a liberatory document instead?

Model of Barnes’s final SUNY Purchase master plan with designs by several other architects, prepared for the Museum of Modern Art exhibition “Architecture for the Arts,” 1971.

Model of Barnes’s final SUNY Purchase master plan with designs by several other architects, prepared for the Museum of Modern Art exhibition “Architecture for the Arts,” 1971.

SESAH Annual Conference 2022

Master Planning a New Urban Spectacle: The Galleria, Houston, ca. 1970

Conference Presentation, November 2022

Designed by St.

Louis-based Gyo Obata of Hellmuth, Obata, and Kassabaum (HOK) for the famed

developer Gerald D. Hines Interests, Houston’s Galleria was a multi-purpose development with

a fully-conditioned environment chilled enough to include a year-round indoor

skating rink. HOK’s master plan organized built space within gridded modules

made visible on the exterior. Module sizes varied based on each building’s

purpose—hotels featured a slightly shorter floor-to-floor height than office

buildings, for example, and the shopping arcade had much larger structural

spans. Still, retailer identity necessitated more substantial variation in the

case of anchor stores like Neiman Marcus. On the one hand, the Galleria suburbanized the urban spectacle

of the commercial arcade and the world-unto-itself of the classic department

store. On the other hand, it upgraded the distinctive spatial format of the

shopping mall to the level of a new city center rather than a meager substitute.

But it also created a placeless “hyperspace” indifferent to its humid

subtropical surroundings. This paper asks: was this the end of the urban commercial spectacle

or the moment of its rebirth?

A busy night at the Houston Galleria’s famous ice rink; view showing reflections in the mirrored ceiling above the frozen surface (Houston Chronicle)

A busy night at the Houston Galleria’s famous ice rink; view showing reflections in the mirrored ceiling above the frozen surface (Houston Chronicle)

SECAC 2022

Labor in and on the Landscape: Architectures of Organizing in the Mining Town, 1875–1925

Conference Presentation, October 2022

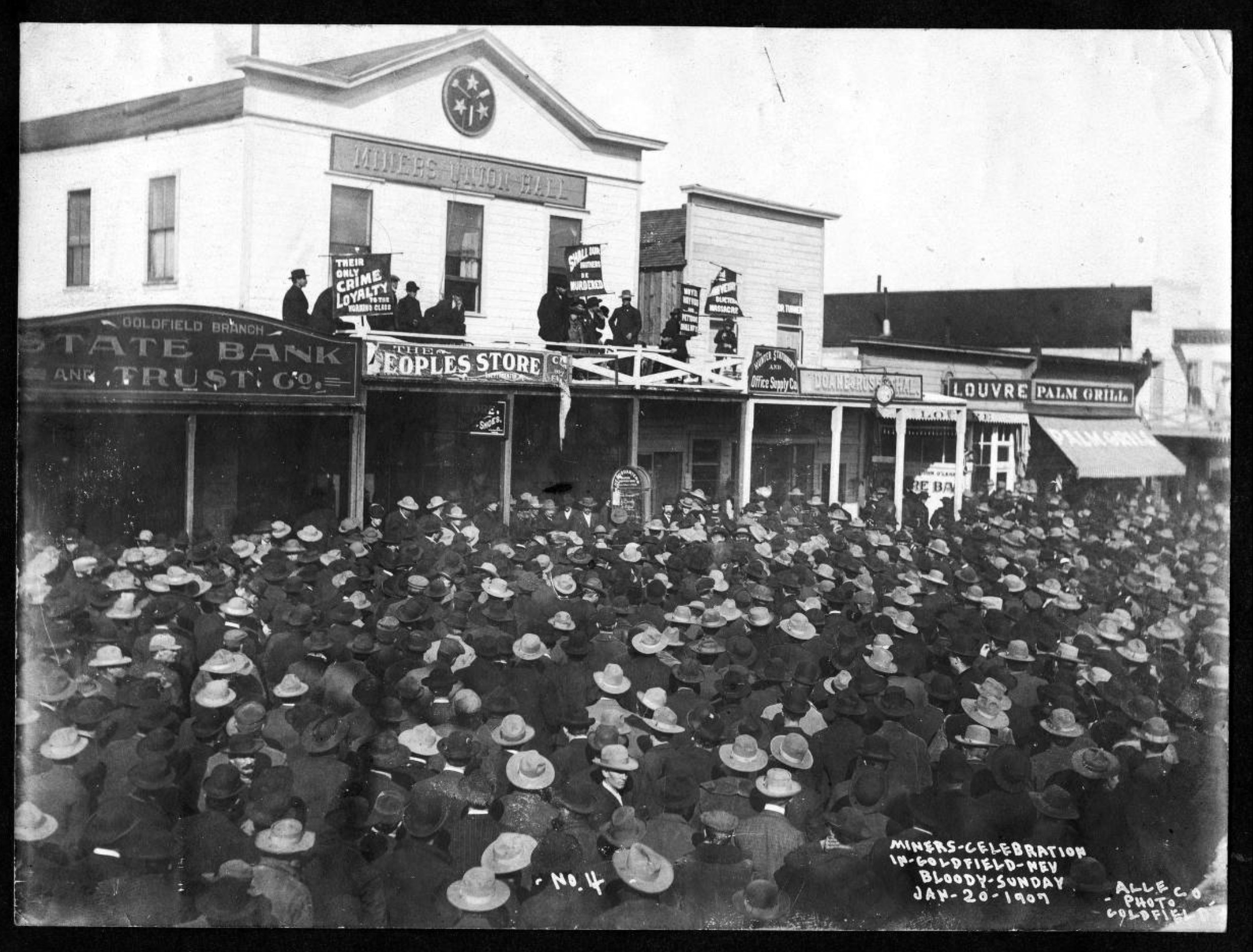

An evolution and expansion of prior work on Miners’ Union Halls, this paper is part of a larger project on architecture by/for organized labor. This research has been an exercise in

material compilation and archive construction. Miners union locals were

decentralized in their governance, and the records of most have been lost. The general pattern was, as one historian

has put it, that the union hall was not merely a place for formal organizing

meetings but also “the center of social and intellectual life” for miners. This

pattern played out simultaneously in many boomtowns across the West where

miners’ working conditions spurred the formation of unions. In this paper I sketched the history of

this building type through a handful of singular cases from Nevada’s Comstock Lode and South Dakota’s Homestake Mine to the streets of Goldfield, Nevada and Butte, Montana, showing its evolution from its origins to a

symbolic demise at the hands of one union’s own members.

Research supported by a collections engagement grant from the Utah Museum of Fine Arts / J. Willard Marriott Library.

Western Federation of Miners Local no. 220 Union Hall, Goldfield, Nevada serves as the backdrop for a 1907 demonstration on the second anniversary of the “Bloody Sunday” massacre in St. Petersburg, Russia. UNLV Digital Collections.

Research supported by a collections engagement grant from the Utah Museum of Fine Arts / J. Willard Marriott Library.

Western Federation of Miners Local no. 220 Union Hall, Goldfield, Nevada serves as the backdrop for a 1907 demonstration on the second anniversary of the “Bloody Sunday” massacre in St. Petersburg, Russia. UNLV Digital Collections.

Construction History Society of America 7th Biennial

Housing

Solidarity: Building by and for the United Auto Workers in Detroit, 1935–196X

Conference Presentation, June 2022

An

early dispatch from a research project on the architectural and construction

history of organized labor in the United States, in this paper I will narrate

the strata of twentieth-century history on one particular site on the north

side of Detroit, which since 1951 has served as headquarters of the UAW. Reaching

backward to the founding of the union years earlier and forward to the strange,

presently uncertain fate of the union’s headquarters building, known as

Solidarity House, this history reveals the necessity of space and the functions

of construction in the building — and maintenance — of class solidarity. Designed

by Oscar Stonorov (a Philadelphia architect known primarily for labor union

housing in that city and a personal friend of UAW President Walter Reuther) Solidarity

House was located on the same site as an Italianate home once occupied by Edsel

Ford, son of Henry and President of Ford Motor Company until his untimely death

in 1943. The residence was originally built for lumber, railroad, and real

estate baron Albert L. Stephens, making the history of this single site a

microcosm for Detroit as a whole from Gilded Age to manufacturing mecca to the

power-sharing détente established between labor and industry by midcentury.

Stonorov’s design

aimed to capture the spirit of this optimistic alliance through the

now-familiar forms, materials and construction methods of modernist

architecture. What made Solidarity House unusual was its function. Unlike the

slick symbols of consolidated corporate power that populate most textbooks on

modernism, this was a building by and for laborers and their elected leaders.

Demolition of the Stephens/Ford House on the property of UAW Solidarity House, Jefferson Avenue, Detroit, ca. late 1950s. Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University.

Demolition of the Stephens/Ford House on the property of UAW Solidarity House, Jefferson Avenue, Detroit, ca. late 1950s. Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University.